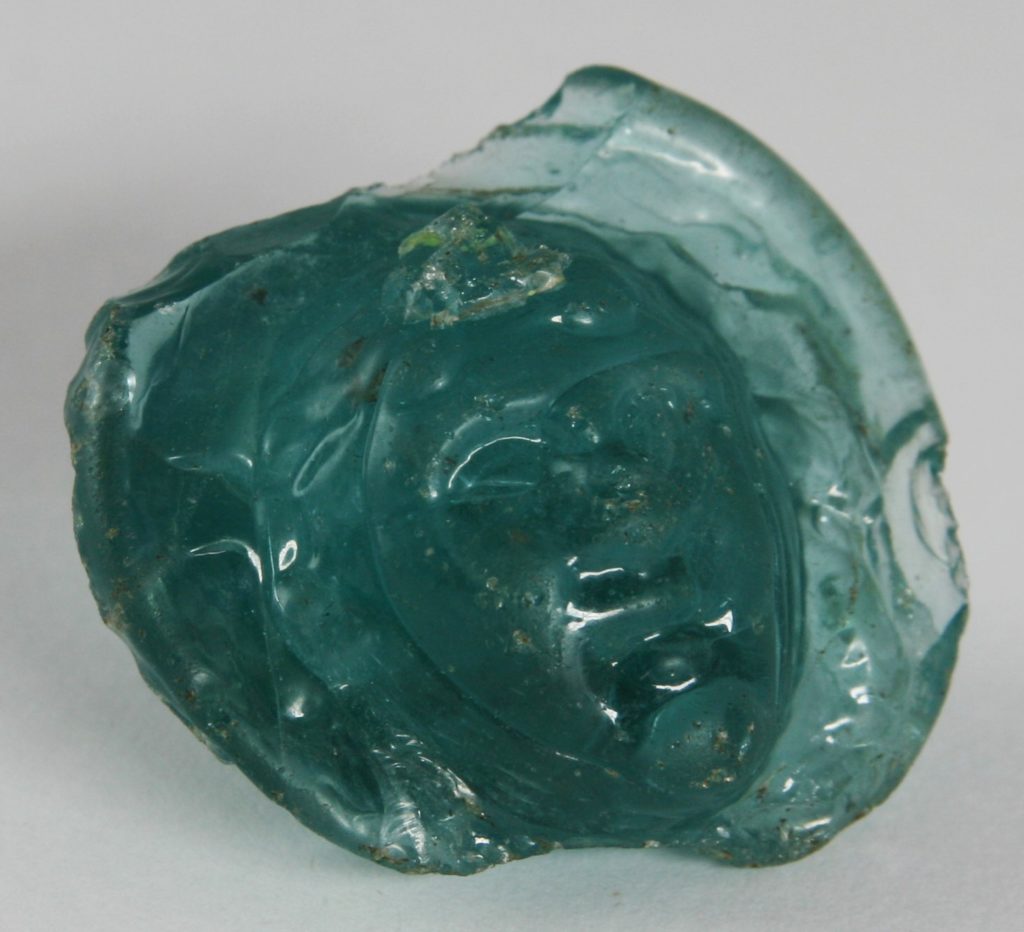

Roman glass head

A tale of revelry and ritual

From: Poole Museum

This enigmatic face is thought to be Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and revelry. The tiny glass piece would have originally hung from a highly-decorated Roman wine glass.

Roman drinking glasses were often decorated with likenesses of Bacchus and his attendants – male satyrs and female maenads.