Amesbury Archer

Mysterious 'archer' who wasn't a hunter!

From: The Salisbury Museum

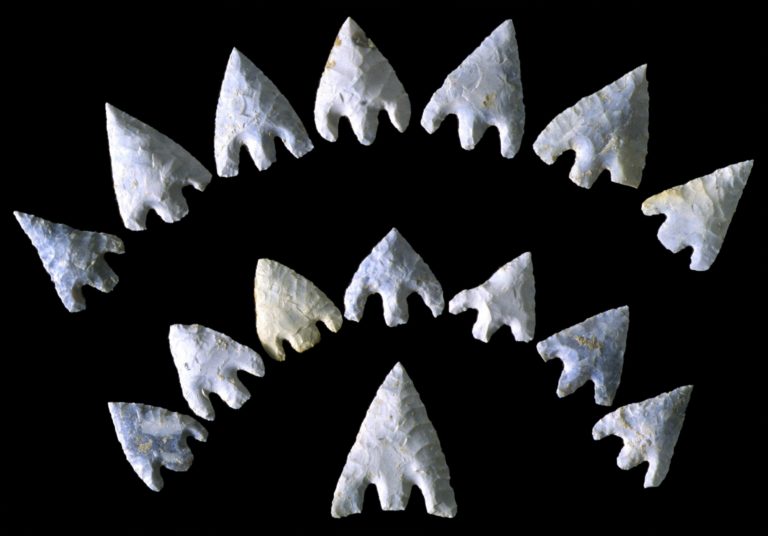

The grave of the Amesbury Archer is one of the most important discoveries in Europe. Found near Stonehenge, the burial is over 4,000 years old. But despite the name, the ‘archer’ was probably one of the earliest metalworkers in England.