Curator’s Insights

This object was highlighted by Sophia, art student and gallery steward for Dorset Museum & Art Gallery.

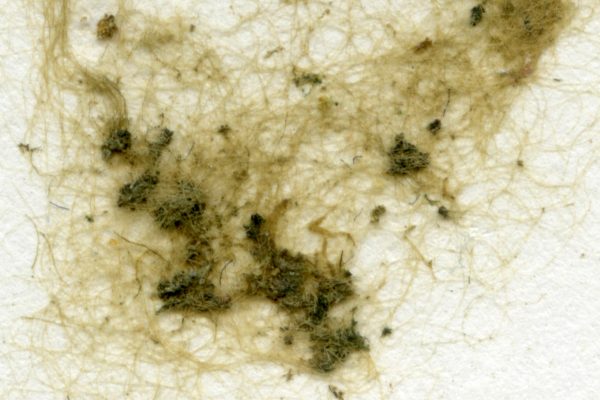

“When I was a child, I would go down to a broad sandy beach in North Cornwall – very early in the morning – to surf with my grandad. The thrill of catching a wave and the peace of being with it as I travelled with the water, grounded me, making me feel connected and alive. After, I’d spend hours in the rock pool watching the different seaweeds move so effortlessly with the currents; the long, fine strands mesmerized me, so content just to be, without resistance or concern.

For me, the sound and motion of water is symbolic of life itself, it’s like the pulse of the world – fluid, changeable, constant. Algae exist in the state, they move with it. Taking the time to just be in that same floating state helped put things in perspective when I felt stressed or anxious and made me feel peaceful and content. It helps me understand that, like algae, our primary function is to be.

There is an honesty to it which reminds me of us and our place in this world – that we’re a part of it, and even if we see our function within it, it moves us as much as we move within it.

Now when I see these algae – in ponds, or rivers, or back on the same beach in those rock pools – I feel that same comfort and connection.”