The tunic was brought home from the Boer War and kept by the soldier upon discharge from the army in 1902. During the First World War, it was cut up and made into a child’s coat, with the addition of fake fur trimmings around the collar, cuffs, and pockets, probably from a muff. Three buttons are missing. It is 680mm (26 inches) long, about the size for a five year old.

The style of the coat appears to have been on trend for young children at the time, as it is a common sight in printed images and other collections. During the First World War, there was a shortage of some fabrics. Wool was needed for uniforms and linen for aircraft covering. People were encouraged to adapt and re-use garments, which happened with the child’s red coat in the Salisbury Museum’s collection – an early example of sustainable fashion. Recycling and repurposing continue in many other ways. Many garments worn during official parades like the trooping of the colour, are antiques handed down through generations or recycled. Many swords date back to the Boer War, with buttons on red tunics being recast dozens of times, and some Bearskin caps still have musket ball holes from use in the nineteenth century.[ii]

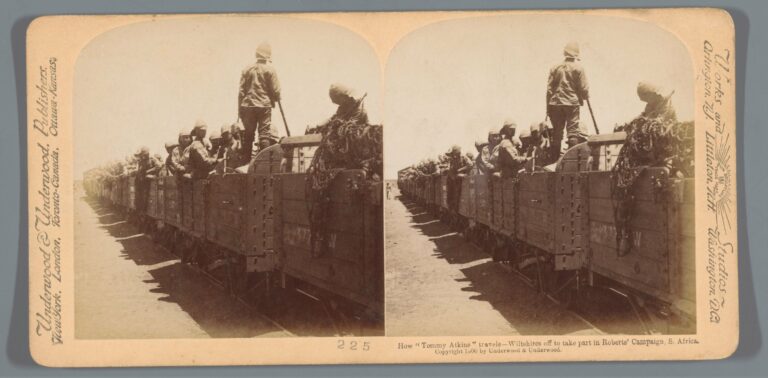

![Child's red coat with black fur collar and cuffs and pocket trims, With kind permission of Salisbury Museum ©]](https://www.wessexmuseums.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/SM-Boer-war-childs-coat-768x1152.jpg)